Review 2018 Cranston Artist Exchange 13th One Act Play Festival

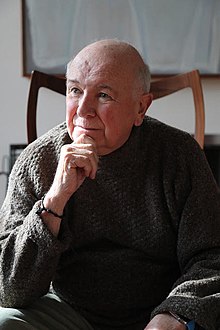

| Terrence McNally | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1938-xi-03)November iii, 1938 St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S. |

| Died | March 24, 2020(2020-03-24) (anile 81) Sarasota, Florida, U.S. |

| Occupation | Playwright, librettist |

| Teaching | B.A. in English |

| Alma mater | Columbia University |

| Flow | 1964–2020 |

| Spouse | Tom Kirdahy (m. ) |

Terrence McNally (Nov iii, 1938 – March 24, 2020) was an American playwright, librettist, and screenwriter.

Described as "the bard of American theater"[1] and "one of the greatest contemporary playwrights the theater world has yet produced,"[2] McNally was the recipient of 5 Tony Awards.[three] He won the Tony Award for Best Play for Love! Valour! Compassion! and Master Course and the Tony Laurels for Best Book of a Musical for Osculation of the Spider Woman and Ragtime, [four] [v] and received the 2019 Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement.[6] [7] He was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in 1996, and he also received the Dramatists Guild Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and the Lucille Lortel Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2018, he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Messages, the highest recognition of artistic merit in the United States. His other accolades included an Emmy Accolade, 2 Guggenheim Fellowships, a Rockefeller Grant, iv Drama Desk-bound Awards, ii Lucille Lortel Awards, 2 Obie Awards, and three Hull-Warriner Awards.[viii]

His career spanned half dozen decades, and his plays, musicals, and operas were routinely performed all over the world.[9] He besides wrote screenplays, teleplays, and a memoir.[10] [eleven] Active in the regional and off-Broadway theatre movements besides as on Broadway, he was one of the few playwrights of his generation to have successfully passed from the avant-garde to mainstream acclaim.[12] His work centered on the difficulties of and urgent demand for man connection. He was vice-president of the Quango of the Dramatists Guild from 1981 to 2001.

He died of complications from COVID-19 on March 24, 2020, at Sarasota Memorial Infirmary in Florida.[13]

Early life and pedagogy [edit]

McNally was born November 3, 1938, in St. Petersburg, Florida, to Hubert Arthur and Dorothy Katharine (Rapp) McNally,[xiv] two transplanted New Yorkers from Irish Catholic backgrounds.[fifteen] [16] His parents ran a seaside bar and grill called The Pelican Club, just after a hurricane destroyed the establishment, the family briefly relocated to Port Chester, New York, then to Dallas, Texas, and finally to Corpus Christi, Texas. There Hubert McNally purchased and managed a Schlitz beer distributorship,[17] and McNally attended Westward.B. Ray Loftier School. Despite his distance from New York City, McNally'south parents enjoyed Broadway musicals. When McNally was eight years onetime, his parents took him to see Annie Go Your Gun, starring Ethel Merman, and on a subsequent outing, McNally saw Gertrude Lawrence in The King and I.[eighteen] McNally later said: "When I saw On the Boondocks, with Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly and Jules Munshin with the Staten Island Ferry and the Empire State Edifice, I said: 'That's where I want to live.' I've never regretted information technology."[xix] [a] In high school McNally was encouraged to write by a gifted English language teacher, Maurine McElroy (1913–2005).[b]

He enrolled at Columbia College in 1956. There he especially enjoyed Andrew Chiappe'southward 2-semester course on Shakespeare in which students read Shakespeare's plays in roughly the club of their limerick.[22] He joined the Boar'south Head Society[23] and wrote Columbia's annual Varsity Show, which featured music by fellow student Edward 50. Kleban and directed past Michael P. Kahn. He graduated in 1960 with a B.A. in English language and membership in Phi Beta Kappa Society.[12] [24] In 1961, McNally was hired by novelist John Steinbeck to tutor his two teenage sons as the Steinbeck family took a cruise effectually the earth.[c] On the cruise McNally completed a draft of what became the opening act of And Things That Go Bump in the Nighttime. Steinbeck asked McNally to write the libretto for a musical version of the novel Eastward of Eden.[25]

Career [edit]

Early career [edit]

After graduation, McNally moved to Mexico to focus on his writing, completing a comedy play which he submitted to the Actors Studio in New York City for product. While the play was turned downward by the acting school, the Studio was impressed with the script, and McNally was invited to serve as the Studio's phase manager so that he could gain practical knowledge of theater. His primeval full-length play, This Side of the Door, deals with a sensitive boy'southward boxing of wills with his overbearing father and was produced in an Actor's Studio Workshop in 1962, featuring a young Estelle Parsons.[12] Starting a career that covered both off-Broadway and Broadway, his plays cried out against Vietnam, satirized stale family dynamics, mocked sexual mores and became a role of the social protest movement of the 1960s and early 1970s.[26]

In 1964, his next play And Things That Go Crash-land in the Night put homosexuality squarely on phase which brought him the ire of New York City'due south bourgeois theatre critics.[27] It opened at the Royale Theatre on Broadway to by and large negative reviews. The play explores the psycho-social dynamic of anxiety that leads one to preemptively and defensively accuse others of creating bug that in authenticity result from one'south ain insecurity. McNally after said, "My first play, Things That Become Crash-land in the Night, was a big bomb. I had to begin all over over again."[eleven] Nevertheless, the producer, Theodore Mann dropped the toll of tickets to $ane.00 which immune the production to run with sold-out houses for three weeks.[28]

Next (1968), which brought him his greatest early acclaim and was directed by Elaine May and starred James Coco, follows a married, center-aged, businessman who has been mistakenly drafted into the military. Botticelli (1968) centers on two American soldiers continuing guard in the jungle while making a game of the neat names in Western Civilization. ¡Cuba Si! (1968) satirizes the disdain that many Americans experience for the idea of revolution though United States was itself born out of a revolution. It starred Melina Mercouri. In Where Has Tommy Flowers Gone? (1971) he celebrates while mourning the ineffectiveness of the American youth motility'south conviction to "blow this state up so we can start all over again." Sweetness Eros (1968) is most a beau who professes his love to a naked woman he has gagged and spring to a chair. In Allow It Bleed (1972) a young couple showers and becomes convinced an intruder is lurking on the other side of the shower mantle. These and his other early on plays, including Bout (1967), Witness (1968), and Bringing It All Dorsum Abode (1970), and Whiskey (1973), course a dark satire on American moral complacency.[12]

McNally turned to comedy and farce, beginning with Noon (1968), a sexual farce revolving around five strangers who are lured to an apartment in lower Manhattan by a personal advertisement. Bad Habits, which satirizes American reliance upon psychotherapy, premiered at the John Drew Theatre in East Hampton, New York, in 1971 starring Linda Lavin. It transferred to the Booth Theatre on Broadway in 1974 and garnered an Obie Award. The Ritz is a farce centering on a straight homo who inadvertently takes refuge in a Mafia-owned gay bathhouse. It opened at the National Theatre in Washington, D.C., and moved to the Longacre Theatre on Broadway in 1975. Robert Drivas, then McNally's romantic partner, directed both productions.[29] [12] McNally adapted the play for the movement picture, The Ritz (1976), directed by Richard Lester. In 1978, McNally wrote Broadway, Broadway, which failed in its Philadelphia endeavour-out starring Geraldine Folio. Rewritten and retitled Information technology's Just a Play, it premiered in off-Broadway in 1985 at Manhattan Theatre Club directed by John Tillinger and starring Christine Baranski, Joanna Gleason, and James Coco.[12] [29]

Mid-career [edit]

Subsequently the failure of Broadway, Broadway and living briefly in Hollywood, he returned to New York Metropolis and formed an artistic relationship with Manhattan Theatre Club. The rapid spread of AIDS fundamentally inverse his writing.[12] McNally but became truly successful with works such as the off-Broadway product of Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune and its screen adaptation with stars Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer. His beginning Broadway musical was The Rink in 1984, a project he joined after the score past composer John Kander and lyricist Fred Ebb had been written. In 1990, McNally won an Emmy Award for Best Writing in a Miniseries or Special for Andre's Mother, a drama about a woman coping with her son's death from AIDS. A yr later, in Lips Together, Teeth Apart, two married couples spend the Fourth of July weekend at a summer house on Fire Island. They are all afraid to use the puddle given that its owner who has just died of AIDS. It was written for Christine Baranski, Anthony Heald, Swoosie Kurtz (taking the place of Kathy Bates), and frequent McNally collaborator Nathan Lane, who had also starred in The Lisbon Traviata.[thirty] [31]

With Kiss of the Spider Woman (based on the novel past Manuel Puig) in 1992, McNally returned to the musical stage, collaborating with Kander and Ebb on a script which explores the circuitous relationship between two men jailed together in a Latin American prison. Osculation of the Spider Woman won the 1993 Tony Honour for All-time Book of a Musical, the offset of McNally's four Tony Awards. He collaborated with Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens on Ragtime in 1997, a musical adaptation of the E. L. Doctorow novel, which tells the story of Coalhouse Walker Jr., a blackness musician who demands retribution when his Model T is destroyed by a mob of white troublemakers. The musical too features such historical figures as Harry Houdini, Booker T. Washington, J. P. Morgan, and Henry Ford. For his libretto, McNally won his 3rd Tony Laurels. Ragtime finished its Broadway run on January sixteen, 2000. A revival in 2009 closed subsequently only two months.[32]

McNally's other plays from this flow include 1994'south Love! Valour! Compassion!, with Lane and John Glover, which examines the relationships of viii gay men; information technology won McNally his 2nd Tony Honour. Master Class (1995); a character study of legendary opera soprano Maria Callas, which starred Zoe Caldwell and won the Tony Laurels for Best Play, McNally'southward fourth; and the least-known of the group, Dedication or The Stuff of Dreams (2005) with Lane and Marian Seldes.[33]

McNally's Corpus Christi (1997) became the subject of protests. In this retelling of the story of Jesus' birth, ministry, and decease, he and his disciples are portrayed as homosexual. The play was initially canceled because of death threats against the board members of the Manhattan Theatre Club, which produced the play.[34] The board relented afterward several other playwrights, including Athol Fugard, threatened to withdraw their plays if Corpus Christi was not produced. A crowd of almost two,000 protested the play as blasphemous at its opening. After it opened in London in 1999, a group chosen the "Defenders of the Messenger Jesus" issued a fatwa sentencing McNally to decease.[35] In 2008, the play was revived in New York City at Rattlestick Playwrights Theatre. Reviewing this production for The New York Times, Jason Zinoman wrote that "without the dissonance of controversy, the play tin finally be heard. Staged with admirable delicacy... the work seems more personal than political, a coming-of-age story wrapped in religious sentiment."[36]

Late career [edit]

In 2000, McNally partnered with composer and lyricist David Yazbek to write the musical The Full Monty, which was directed past Jack O'Brien and choreographed by Jerry Mitchell. Information technology had an initial run at The One-time Globe Theatre and and then transferred to the Eugene O'Neill Theatre on Broadway. The opening dark bandage included Patrick Wilson, Andre De Shields, Jason Danieley, Kathleen Freeman, Emily Skinner, and Annie Golden.[37] It was nominated for 12 Tony Awards including for McNally'southward book.[38] It afterward transferred to the Prince of Wales Theater in London'southward West End.[39]

McNally collaborated on several new American operas.[40] His voice may exist more familiar with opera fans than theater-goers, as for nearly 30 years (1979-2008) he was a member of the Texaco Opera Quiz panel that fielded questions during the weekly Alive from the Met radio broadcasts.[12] He wrote the libretto for Dead Man Walking, his accommodation of Sister Helen Prejean'southward book, with a score by Jake Heggie. The opera had its globe premiere at San Francisco Opera in 2000 and afterwards received two commercial recordings and over twoscore productions worldwide, making it "ane of the almost successful American operas in recent decades."[41] In 2007, Heggie composed a sleeping accommodation opera, Three Decembers, with a libretto by Gene Scheer based on a text McNally had created in 1999 for a Christmas concert to benefit Broadway Cares/Disinterestedness Fights AIDS, Some Christmas Letters (and a Couple of Phone Calls, Likewise).[42] [43] In Oct 2015, Dallas Opera presented Great Scott with an original libretto by McNally and a score past Heggie. The new opera starred Joyce DiDonato and Frederica von Stade and was directed past Jack O'Brien.[44]

The Kennedy Center presented 3 of McNally's plays that focus on opera under the heading Nights at the Opera, in March 2010. It included a new play, Golden Age; Master Class, starring Tyne Daly; and The Lisbon Traviata, starring John Glover and Malcolm Gets.[45] [46] [47] Golden Age afterward ran Off-Broadway at the Manhattan Theatre Club New York Metropolis Middle – Stage I from November 2012 to January 2013.[48]

In 2001, McNally started what became a 15-year developmental process towards Broadway with the musical The Visit, for which he wrote the book. The music is written by John Kander and the lyrics by Fred Ebb. Adapted from Friedrich Dürrenmatt'southward 1956 satire, The Visit is the story of a widow who has clustered enormous sums of wealth and returns to her hometown to seek revenge on the villagers who scorned her in her youth. The project originally starred Angela Lansbury who departed the procedure to intendance for her ailing husband. Chita Rivera became the new star and The Visit had its outset production at The Goodman Theater in Chicago in 2001. The commencement preview was held but ten days afterward the September 11 attacks, and the producers were unable to go many investors or critics from New York City to wing to Chicago. In 2004, Fred Ebb, the lyricist, died. Its next regional production occurred in 2008 at The Signature Theatre exterior of Washington D.C. In 2014, under the direction of John Doyle and starring Chita Rivera and Roger Rees, The Visit had a new product at Williamstown Theatre and then transferred to Broadway at The Lyceum Theatre in 2015.[49] [50] The musical was nominated for v Tony awards including for McNally's book.[51]

Continuing his piece of work on librettos, McNally partnered with his collaborators on Ragtime, Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens, to write the musical A Man of No Importance which premiered at Lincoln Heart in 2002 and was directed by Joe Mantello.[52] He also wrote the libretto for Chita Rivera: The Dancer's Life, in 2005, another collaboration with Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens, which began at The Former Globe and later transferred to Broadway at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre.[53]

In 2004, Principal Stages presented McNally's The Stendhal Syndrome, which according to McNally explores "how art tin can affect us emotionally, psychologically, and erotically." The play starred Isabella Rossellini and Richard Thomas and was directed by Leonard Foglia.[54] In 2007, Philadelphia Theatre Company presented Some Men, which explores the evolution of gay relationships and aforementioned-sex marriage. Information technology went on to 2d Phase Theatre in New York and was directed past Trip Cullman.[55] That same twelvemonth McNally'south drama Deuce ran on Broadway at the Music Box Theater for a limited engagement in 2007 for 121 performances. Directed by Michael Blakemore, the play starred Angela Lansbury, in her return to Broadway afterward more than 20 years, and Marian Seldes.[56]

And Away Nosotros Go premiered Off-Broadway at the Pearl Theatre in November 2013, with direction by Jack Cummings 3 and featured Donna Lynne Champlin, Sean McNall and Dominic Cuskern.[57] The play takes place over several millennia covering the most pivotal moments in dramatic history entwined with a mod-solar day story of a struggling theatre visitor.[58] McNally said that "Information technology'due south very much written for the Pearl, the company that has kept the faith for the great classic plays. There are whole seasons in New York when I don't recall a single classic play would take been performed if it hadn't been for the Pearl... I think it's really important. I write new plays for a living; I certainly don't think theatre should exist just revivals, just in that location has always got to be a place for Chekhov, Ibsen, Shakespeare, Moliere and Aeschylus."[59]

Mothers and Sons starring Tyne Daly and Frederick Weller opened on Broadway at the John Golden Theatre, where Primary Course had its premiere, on March 24, 2014 (February 23, 2014 in previews).[lx] Mothers and Sons premiered at the Bucks County Playhouse (Pennsylvania) in June 2013.[61] Vermont Stage opened its production January 27, 2016[62] at FlynnSpace in Burlington, Vermont. The play is an expansion on his 1988 drama Andre's Female parent, which was prepare at a memorial service for a victim of the AIDS crisis.Mothers and Sons likewise marked the first time a legally wed gay couple was portrayed on Broadway.[63] Information technology was nominated for 2 Tony Awards including for All-time Play.[64]

McNally's Fire and Air premiered Off-Broadway at Archetype Phase Company on Feb 1, 2018.[65] The play explores the history of the Ballets Russes, the Russian ballet company, with a detail focus on Sergei Diaghilev, the ballet impresario, and Vaslav Nijinsky, the dancer and choreographer. It featured the actors Douglas Hodge, Marsha Mason, Marin Mazzie, John Glover, and Jay Armstrong Johnson and was directed by Tony Laurels-winner John Doyle.[66]

On May 29, 2019, a revival of Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune opened on Broadway at the Broadhurst Theatre. The product starred Audra McDonald and Michael Shannon, and was directed by Arin Arbus in her Broadway debut.[67]

In June 2019, to mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, an effect widely considered a watershed moment in the modernistic LGBTQ rights movement, Queerty named him one of the Pride50 "trailblazing individuals who actively ensure society remains moving towards equality, acceptance and dignity for all queer people".[68]

McNally received a Special Tony Award for Lifetime Accomplishment in 2019.[69] [70]

Personal life [edit]

In his early years in New York Metropolis, McNally'due south interest in theatre brought him to a party where, departing, he shared a cab with Edward Albee, who had recently written The Zoo Story and The Sandbox. They functioned as a couple for over four years during which Albee wrote The American Dream and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? [12] He was frustrated by Albee'due south lack of openness almost his sexuality. McNally later said: "I became invisible when press was around or at an opening night. I knew it was wrong. It's so much work to live that way."[71] After his relationship with Albee, McNally entered into a long-term relationship with the actor and manager Robert Drivas.[12] Drivas and McNally broke up as a couple in 1976; they remained shut friends until Drivas died of AIDS-related complications 10 years afterwards.[29]

McNally was partnered to Tom Kirdahy, a Broadway producer and a former civil rights chaser for not-for-profit AIDS organizations, post-obit a civil wedlock ceremony in Vermont on December 20, 2003.[72] [73] They married in Washington, D.C. on April half dozen, 2010. In celebration of the Supreme Courtroom'due south decision to legalize aforementioned-sex marriage in all l states, they renewed their vows at New York Metropolis Hall with Mayor Bill de Blasio, Kirdahy's college roommate,[74] officiating on June 26, 2015.[75] [76]

When given his Tony for Lifetime Achievement in June 2019, he began his acceptance speech saying "Lifetime achievement. Non a moment too soon." He wore a cannula and appeared short of jiff.[77] McNally died at Sarasota Memorial Infirmary in Sarasota, Florida, on March 24, 2020, at the age of 81, from complications of coronavirus disease 2019 during the COVID-19 pandemic. He had previously overcome lung cancer in the late 1990s that cost him portions of both his lungs due to the disease, and he was living with COPD at the time of his death.[thirteen]

On theater [edit]

For McNally, the nigh important role of theatre was to create community and bridge rifts opened between people by differences in religion, race, gender, and particularly sexual orientation.[78]

In an accost to members of the League of American Theatres and Producers he remarked, "I remember theatre teaches u.s.a. who we are, what our order is, where we are going. I don't think theatre can solve the issues of a gild, nor should it exist expected to ... plays don't practise that. People exercise. [But plays can] provide a forum for the ideas and feelings that can pb a society to decide to heal and alter itself."[79]

Annal [edit]

McNally donated his papers to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The archive includes all of his major works for stage, screen, and goggle box, besides equally correspondence, posters, production photographs, programs, reviews, awards, speeches, and recordings. It is an open archive.[lxxx] He had previously deposited his papers at the University of Michigan. His loftier school English language teacher, Maurine McElroy, who had since become caput of freshman English at the University of Texas, influenced his choice of Texas.[19]

Documentary [edit]

Terrence McNally: Every Human action of Life, a documentary almost McNally'south life and career, aired on PBS on June 14, 2019, as function of their American Masters series.[81] [82] The motion-picture show features new interviews with McNally in add-on to conversations with his friends and collaborators, including F. Murray Abraham, Christine Baranski, Tyne Daly, Edie Falco, John Kander, Nathan Lane, Angela Lansbury, Marin Mazzie, Audra McDonald, Rita Moreno, Billy Porter, Chita Rivera, Doris Roberts, John Slattery and Patrick Wilson, plus the voices of Dan Bucatinsky, Bryan Cranston and Meryl Streep.[82] Charles McNulty, reviewing the film for the Los Angeles Times, wrote, "If you can know a person by the company he keeps, you tin can judge a playwright by the talent that sticks past him. By this measure out, Terrence McNally was one of the most of import dramatists of the last 50 years."[83]

Writing credits [edit]

Plays:

- And Things That Go Bump in the Night (1964)

- Botticelli (1968)

- Sweet Eros (1968)

- Witness (1968)

- ¡Cuba Si! (1968)[84]

- Bringing It All Back Home (1969)[84]

- Noon (1968), second segment of Morn, Apex and Nighttime

- Apple Pie [xx]

- Three 1-act plays: Tour, Next (in two versions), and Botticelli

- Next (1969)

- Where Has Tommy Flowers Gone? (1971)

- Bad Habits (1974)[85]

- Two one act plays: Ravenswood and Dunelawn

- Whiskey (1973)[86]

- The Tubs (1974), early version of The Ritz

- The Ritz (1975)

- Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (1982)

- It's Only a Play (1986)

- Hope (1988), second segment of Organized religion, Hope and Charity

- Andre's Mother (1988)[d]

- The Lisbon Traviata (1989)

- Prelude and Liebestod (1989)

- Subsequently presented as half of The Stendhal Syndrome (2004)

- Lips Together, Teeth Autonomously (1991)

- A Perfect Ganesh (1993)

- Subconscious Agendas (1994)[87]

- Honey! Valour! Compassion! (1994)

- By the Bounding main, Past the Sea, By the Beautiful Sea (1995)

- Master Form (1995)

- Corpus Christi (1998)

- The Stendhal Syndrome (2004)[88]

- Ii one-act plays: Full Frontal Nudity and Prelude and Liebestod

- Dedication or The Stuff of Dreams (2005)

- Some Men (2006)

- The Sunday Times (2006)[89]

- Deuce (2007)

- Unusual Acts of Devotion (2008)[ninety]

- Gilt Age (2009)[91]

- And Away Nosotros Become (2013)[92]

- Mothers and Sons (2014)[xiii]

- Fire and Air (2018)[93]

Musical Theatre:

- Here's Where I Belong (1968)[94]

- The Rink (1984)

- Kiss of the Spider Woman (1992)[13]

- Ragtime (1996)

- The Total Monty (2000)[13]

- The Visit (2001)

- A Human of No Importance (2002)

- Chita Rivera: The Dancer'south Life (2005)

- Catch Me If You Can (2011)

- Anastasia (2016)

Opera:

- The Food of Love (1999), music past Robert Beaser[95] [e]

- Expressionless Human Walking (2000), music by Jake Heggie[96]

- Three Decembers (2008), music by Jake Heggie, libretto by Cistron Scheer[f]

- Swell Scott (2015), music by Jake Heggie[98]

Film:

- The Ritz (1976)[99]

- Frankie and Johnny (1991)[99]

- Dearest! Valour! Compassion! (1997)

TV:

- Mama Malone (1984)[100]

- Andre's Female parent (1990)[13]

- The Terminal Mile (1992)[101]

- Mutual Ground (2000)[102] [yard]

Awards and nominations [edit]

Tony Awards [edit]

| Year | Piece of work | Category/award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Kiss of the Spider Woman | Best Book of a Musical | Won | [103] |

| 1995 | Dearest! Valour! Compassion! | Best Play | Won | |

| 1996 | Master Course | All-time Play | Won | |

| 1998 | Ragtime | Best Book of a Musical | Won | |

| 2001 | The Full Monty | Best Book of a Musical | Nominated | |

| 2014 | Mothers and Sons | Best Play | Nominated | |

| 2015 | The Visit | Best Book of a Musical | Nominated | |

| 2019 | Special Tony Honour for Lifetime Accomplishment in the Theatre | Received | ||

Drama Desk Awards [edit]

| Year | Work | Category/honour | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | The Ritz | Outstanding New Play (American) | Nominated | [104] |

| 1990 | The Lisbon Traviata | Outstanding New Play | Nominated | [105] |

| 1992 | Lips Together, Teeth Apart | Outstanding New Play | Nominated | [104] |

| 1995 | Love! Valour! Compassion! | Outstanding Play | Won | [106] |

| 1996 | Master Class | Outstanding Play | Won | [107] |

| 1998 | Ragtime | Outstanding Book of a Musical | Won | [108] |

| 2001 | The Full Monty | Outstanding Book of a Musical | Nominated | [109] |

| 2003 | A Man of No Importance | Outstanding Volume of a Musical | Nominated | [110] |

| 2006 | Dedication or The Stuff of Dreams | Outstanding Play | Nominated | [111] |

| 2007 | Some Men | Outstanding Play | Nominated | [112] |

| 2015 | The Visit | Outstanding Book of a Musical | Nominated | [113] |

| 2017 | Anastasia | Outstanding Book of a Musical | Nominated | [114] |

Primetime Emmy Awards [edit]

| Year | Work | Category/award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Andre's Female parent | Outstanding Writing in a Miniseries or a Special | Won | [115] |

Other awards [edit]

- 1966, 1969 Guggenheim Fellowship[116]

- 1974 Obie Award Winner, Distinguished Play – Bad Habits [117]

- 1992 Lucille Lortel Award Winner, Outstanding Play – Lips Together, Teeth Apart [118]

- 1992 Lucille Lortel Award Winner, Outstanding Torso of Work[118]

- 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Drama Nomination – A Perfect Ganesh [119]

- 1995 Obie Award Winner, Playwriting Laurels – Love! Valour! Compassion! [120]

- 1996 inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.[121]

- In 1998, McNally was awarded an honorary degree from the Juilliard School in recognition of his efforts to revive the Lila Acheson Wallace American Playwrights Program with fellow playwright John Guare.[12]

- In 2011 he received the Dramatists Club Lifetime Accomplishment Award.[122]

- In 2013 he was the keynote speaker for the Columbia College class of 2013.[123]

- In 2016, Lotos Club Country Dinner honoree[124]

- In 2018, he was inducted into the American University of Arts and Letters, the highest recognition of artistic merit in the United states.[125]

- 2019 an honorary doctorate from New York University.[126]

Notes [edit]

- ^ He continued: "I feel at domicile in New York, or I feel like a very welcome visitor.... If you actually desire to work in theater and you lot're serious about information technology — and I got serious about this pretty early — it's the only practical city to live in. If you can find a manner. And I was very lucky that this was a much more than welcoming city to new artists in the '60s than it is at present. It's as well expensive to live here now. The immature writers I know live in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens. Nobody can live on the island now. When I got here at 17, I didn't even visit Brooklyn. I wouldn't leave the island, and now young people can't afford to be on the island, but they seem happy and find a way to make ends run across.[19]

- ^ He dedicated both Apple Pie (1968), a collection of 1-act plays, and Frankie and Johnnie to her.[20] [21]

- ^ McNally had been recommended by Molly Kazan, the Steinbecks' neighbor and McNally's mentor at the Playwrights Unit of measurement of the Actors Studio.[25]

- ^ McNally contributed eight minutes to a theater anthology, Urban Blight and later developed it equally Andre's Mother.[xix]

- ^ A one-act opera premiered in an album of three, each with its ain librettist and composer.[95]

- ^ Based on an unpublished McNally text, Some Christmas Messages.[42] [97]

- ^ McNally contributed one act, Mr. Roberts, to this 3 act album.[102]

References [edit]

- ^ "A Conversation With Terrence McNally, the Bard of American Theater". The New York Times. April x, 2019. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Reed, Rex (March 26, 2014). "A Provincial Lady: Tyne Daly Shines in Mothers and Sons". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October xiv, 2016.

- ^ Boehm, Mike (March 24, 2020). "Playwright Terrence McNally, 81, dies of coronavirus-related complications". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved Jan 4, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ "Terrence McNally". Playbill Vault. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ "American Stage Presents Frankie and Johnny in the Claire De Lune". Broadway World.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Special Tony Awards for Lifetime Achievement 2019". www.tonyawards.com . Retrieved Jan 4, 2021.

- ^ Libbey, Peter (June 10, 2019). "2019 Tony Honor Winners: Full List (Published 2019)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ Purcell, Carey (September 11, 2013). "Jason Alexander, Tyne Daly, Cheyenne Jackson and More Will Honor Terrence McNally at Skylight Theatre Company". Playbill. Archived from the original on October six, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ "Playwright Terrence McNally Coming to City This Calendar month". Cumberland Times-News. Oct one, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ "Terrence McNally | Samuel French". world wide web.samuelfrench.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Rader, Dotson (March 24, 2014). "Playwright Terrence McNally: 'The Most Significant Thing a Writer Tin Practice Is Accomplish Someone Emotionally'". Parade. Archived from the original on April fourteen, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j g Frontain, Raymond (April 1, 2013). "Terrence McNally: Theater equally Connection" (PDF). GLBTQ Athenaeum. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 15, 2016. Retrieved October xiv, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Dark-green, Jesse; Genzlinger, Neil (March 24, 2020). "Terrence McNally, Tony-Winning Playwright of Gay Life, Dies at 81". New York Times . Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Galanes, Philip (April x, 2019). "A Conversation With Terrence McNally, the Bard of American Theater". The New York Times.

- ^ O'Doherty, Cahir (June 10, 2015). "Terrence McNally's dearest of Irish energy". Irish gaelic Central. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Terrence McNally Obituary: Usa playwright who charted gay experience". The Irish gaelic Times. Apr four, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Clipped From The Corpus Christi Caller-Times". The Corpus Christi Caller-Times. September 23, 1976. p. 26. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Zinman, Toby Silverman (1997). Terrence McNally: A Casebook. Routledge. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d McNally, Terrence (September 23, 2016). "Tangling with Texas and sexuality in Terrence McNally's plays". Austin American-Statesman (Interview). Interviewed by Michael Barnes.

- ^ a b McNally, Terrence (1968). Apple Pie: 3 One Act Plays. p. 3. ISBN9780822200611 . Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Wolfe, Peter (2013). The Theater of Terrence McNally: A Critical Study. McFarland. p. iii. ISBN9780786474950 . Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ McNally, Terrence. "Accept Five with Terrence McNally '60". Columbia Higher Today (Interview). Interviewed by Michael Nagle. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "History". Columbia Review. May 22, 2014. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ "Columbia College mourns the loss of Terrence McNally CC'60". Columbia College. March 25, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Frontain, Raymond-Jean (August seven, 2010). "McNally and Steinbeck". ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Brusk Articles, Notes and Reviews. 21 (4): 43–51. doi:10.3200/ANQQ.21.4.43-51. S2CID 162345400.

- ^ "Most – Terrence McNally". www.terrencemcnally.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved Nov 22, 2016.

- ^ Hadleigh, Boze (2013). Broadway Babylon: Glamour, Glitz, and Gossip on the Great White Way. Potter/TenSpeed/Harmony. p. 165. ISBN9780307830135.

- ^ Marks, Peter (March xiv, 2010). "Playwright Terrence McNally'southward Love of Opera Takes Centre Stage at Kennedy Heart". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c Frontain, Raymond-Jean (April 30, 2010). "A Preliminary Calendar of the Works of Terrence McNally". ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Manufactures, Notes and Reviews. 23 (ii): 105–123. doi:10.1080/08957691003712272. ISSN 0895-769X. S2CID 162343250.

- ^ Rothstein, Mervyn (July 3, 1991). "Terrence McNally's Four Stars Talk Happily of His 'Lips Together'". New York Times. Archived from the original on January half-dozen, 2017.

- ^ "The Story" [Archived June 24, 2004, at the Wayback Machine dramatists.com, accessed March 26, 2014

- ^ "The Sondheim Review: Mutual admiration, Sondheim and playwright Terrence McNally began a collaboration in 1991, by Raymond-Jean Frontain Archived January sixteen, 2014, at the Wayback Auto readperiodicals.com, Apr 1, 2011

- ^ "Dedication or The Stuff of Dreams Listing" Archived March 8, 2016, at the Wayback Car lortel.org, accessed Feb 29, 2016

- ^ "Censoring Terrence McNally". The New York Times. May 28, 1998. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Fatwa for 'gay Jesus' writer". BBC News. Oct 29, 1999. Archived from the original on November 12, 2006. Retrieved April xix, 2007.

- ^ Zinoman, Jason (October 21, 2008). "At Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, a Modern, Gay You-Know-Who Superstar". The New York Times . Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "The Full Monty". Internet Broadway Database . Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "The Full Monty Awards". Internet Broadway Database . Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Wolf, Matt (March 22, 2002). "The Full Monty". Multifariousness . Retrieved August thirteen, 2018.

- ^ Marks, Peter (March 14, 2010). "Terrence McNally's love of opera takes eye stage at Kennedy Middle". Washington Post . Retrieved Baronial thirteen, 2018.

- ^ von Rhein, John (February 24, 2015). "'Dead Human being' is wrenching music drama in start full area staging". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved Baronial thirteen, 2018.

- ^ a b "Terrence McNally Pens NYC Vacation 'Letters' for Dec. 13–fourteen Benefit Concert". October 18, 2012. Archived from the original on October eighteen, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2020. playbill.com

- ^ Zinko, Carolyne (December seven, 2008). "South.F. Opera To Adapt 'Expressionless Man'/Heggie-McNally piece of work commissioned for 2000-01". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Great Scott". Opera News. October thirty, 2015. Retrieved Baronial xiii, 2018.

- ^ Hetrick, Adam (February ii, 2010). "Casting Consummate for Master Form, with Daly, at the Kennedy Center". Playbill. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- ^ Hetrick, Adam. "Glover and Gets Open up McNally'due south Lisbon Traviata in Washington, D.C. March 25" Archived June v, 2011, at the Wayback Machine playbill.com, March 25, 2010

- ^ Hetrick, Adam."All That Glitters: Bobbie Talks About McNally'southward Golden Age at the Kennedy Heart" Archived March 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine playbill.com, March 29, 2010

- ^ Hetrick, Adam and Jones, Kenneth. "Manhattan Theatre Club announced that Terrence McNally'south backstage-set operatic play Golden Age, starring Emmy Award nominee Lee Pace as a late-in-life composer Vincenzo Bellini, has extended its run through January. 13, 2013" Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Playbill, December 14, 2012

- ^ Wallenberg, Christopher (July 17, 2014). "A Tenacious Evidence Finds a New Stage". New York Times . Retrieved August xiii, 2018.

- ^ Gerard, Jeremy (January 8, 2015). "Chita River's Destination: Broadway'southward Lyceum For 'The Visit'". Borderline . Retrieved Baronial 13, 2018.

- ^ Perkins, Meghan (May 15, 2015). "The Visit Garners V Tony Nominations". Alive Pattern . Retrieved Baronial thirteen, 2018.

- ^ "A Human being of No Importance Who's Who". Lincoln Eye Theatre . Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Oxman, Steven (October 5, 2005). "Chita Rivera: The Dancer's Life". Variety . Retrieved Baronial thirteen, 2018.

- ^ Hernandez, Ernio (Feb xvi, 2004). "Rossellini and Thomas Fall Under McNally's Stendhal Syndrome, Opens Feb. 16". Playbill . Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (March 27, 2007). "eight Decades of Gay Men, at the Chantry with History". New York Times . Retrieved Baronial 13, 2018.

- ^ Hernandez, Ernio (May vi, 2007). "Angela Lansbury and Marian Seldes Open in McNally'south Deuce May half-dozen". Playbill . Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Hetrick, Adam. "World Premiere of Terrence McNally'southward And Away Nosotros Go Opens Off-Broadway Nov. 24" Archived March 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine playbill.com, November 24, 2013

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (November 26, 2013). "Who Knew That Greek Festival Had Such Legs?". New York Times . Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Purcell, Carey (December vi, 2013). "And Away Nosotros Go - Talking Politics and Theatre with Terrence McNally". Playbill . Retrieved August xiii, 2018.

- ^ "The Verdict: Critics Review Terrence McNally's Mothers and Sons, Starring Tyne Daly" Archived Apr 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine playbill.com, March 25, 2014

- ^ Gioia, Michael. "Tyne Daly and Frederick Weller Explore Relationships of Mothers and Sons, Beginning Feb. 23 On Broadway" Archived Feb 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine playbill.com, February 23, 2014

- ^ "Mothers and Sons". Vermont Stage. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016.

- ^ Dziemianowicz, Joe (February 27, 2014). "Terrence McNally's 'Mothers and Sons' arriving on Broadway in a new historic period of gay rights". Daily News . Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Rooney, David (June 10, 2014). "'Mothers and Sons' Calls it Quits on Broadway". The Hollywood Reporter . Retrieved Baronial 13, 2018.

- ^ BWW News Desk. "Terrence McNally'due south Burn AND AIR Begins Tonight at Classic Stage Visitor". BroadwayWorld.com. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Levitt, Hayley (February eight, 2018). "Classic Stage Company Extends Terrence McNally's Fire and Air". Theater Mania . Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Green, Jesse (May 30, 2019). "Review: 'Frankie and Johnny' Were Lovers. So Came Morning". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ "Queerty Pride50 2019 Honorees". Queerty . Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ "Special Tony Awards for Lifetime Achievement 2019". tonyawards.com . Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ McPhee, Ryan (April 25, 2019). "Terrence McNally, Rosemary Harris, and Harold Wheeler to Receive Honorary 2019 Tony Awards". Playbill . Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Pressley, Nelson (March 24, 2020). "Terrence McNally, celebrated playwright who chronicled gay lives, dies at 81 from coronavirus". Washington Postal service . Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Tom Kirdahy on Dear, Police force, Marriage, Producing Theatre, and Making a Difference". HowlRound. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ "Terrence McNally, Thomas Kirdahy". The New York Times. December 21, 2003. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved April nineteen, 2007.

- ^ Flegenheimer, Matt; Grynbaum, Michael M. (June 26, 2015). "Cuomo and de Blasio Find Common Ground in Commemoration of Gay Marriage Decision". The New York Times . Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "De Blasio hosts ceremony in honor of gay marriage decision". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ "Reliable Source – Love, etc.: Playwright Terrence McNally weds partner in D.C." The Washington Mail. Apr half dozen, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Chris (June 12, 2019). "Terrence McNally's lifetime award oral communication at the Tonys was ignored — but it was the well-nigh important of the dark". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Frontain, Raymond-Jean. "McNally Later the 'Gay Jesus' Play". The Gay and Lesbian Review. Archived from the original on October vi, 2014. Retrieved October five, 2014.

- ^ Frontain, Raymond-Jean (November 2013). ""Theatre Matters": Discovering the True Cocky in Terrence McNally'due south Dedication". Journal of Contemporary Drama in English. i (2): 261–78. doi:x.1515/jcde-2013-0021.

- ^ "Terrence McNally: A Preliminary Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Heart". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (May vi, 2019). "Terrence McNally Documentary Airs on PBS June 14". Playbill . Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ a b "Terrence McNally: Every Act of Life | About | American Masters | PBS". American Masters. January 22, 2019. Retrieved September xxx, 2019.

- ^ "Review: PBS documentary of playwright Terrence McNally celebrates a master of connection". Los Angeles Times. June 13, 2019. Retrieved September xxx, 2019.

- ^ a b "Dramatists Play Service, Inc, Terrence McNally", Book/Item: ¡Cuba SI!, BRINGING IT ALL Back Dwelling, LAST GASPS, ISBN 978-0-8222-0257-8

- ^ McNally, Terrence (March 10, 1974). "He Won't Kick his 'Bad Habits'". The New York Times (Interview). Interviewed by Guy Flatley.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (April xxx, 1973). "Phase: 'Whiskey' Opens: Comedy by McNally Is at St. Clements The Cast". New York Times . Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ Frontain, Raymond-Jean (2003). Reclaiming the Sacred: The Bible in Gay and Lesbian Literature. Psychology Press. p. 238. ISBN9781560233558 . Retrieved March 31, 2020.

a one-act play that McNally wrote in response to the Robert Mapplethorpe controversy

- ^ Brantley, Ben (Feb 17, 2004). "A Maestro Hears Music As Echoes of His Ego". The New York Times . Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ The Lord's day Times Archived Nov i, 2016, at the Wayback Automobile, play details

- ^ Jones, Kenneth. Unusual Acts of Devotion Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Motorcar Playbill, June 10, 2009

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (March 3, 2009). "McNally's Golden Age Will Premiere in Philadelphia Before Playing DC". Playbill . Retrieved March 24, 2020. ,

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (November 26, 2013). "Who Knew That Greek Festival Had Such Legs?". The New York Times . Retrieved March 24, 2020. ,

- ^ Clement, Olivia. "Terrence McNally'southward Fire and Air, With Marin Mazzie, Jay Armstrong Johnson, and More than, Begins Off-Broadway" Archived January 17, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Playbill, January 17, 2018

- ^ "Librettist Disowns Work on Musical". The New York Times. February 9, 1968. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

Terence McNally ... has asked to have his name removed from the program.

- ^ a b Blackness, Cheryl; Friedman, Sharon (2019). Modern American Drama: Playwriting in the 1990s: Voices, Documents, New Interpretations. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 206. ISBN9781350153653 . Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ Kosman, Joshua (October nine, 2000). "'Walking' Tall: Opera's Expressionless Human being is a masterpiece of music, words and emotions". San Francisco Chronicle . Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Sigman, Matthew (July 2015). "Composing a Life". Opera News . Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Kosman, Joshua (Oct 31, 2015). "Heggie's Great Scott fumbles effort to team up opera, football game". San Francisco Chronicle . Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ a b Zinman, Toby Silverman (1997). Terrence McNally: A Casebook. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN9781135595982 . Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ O'Connor, John J. (March 7, 1984). "'Mama Malone,' CBS Series, Begins". New York Times.

- ^ Leonard, John (October 12, 1992). "Tv set. One thousand Performance". New York Magazine. p. 66. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Goodman, Walter (January 28, 2000). "Tv set Weekend: From Gay Bashing to Gay Wedlock". The New York Times . Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "Nominees". tonyawards.com . Retrieved November xv, 2019.

- ^ a b "Internet Broadway Database". www.ibdb.com . Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "1990 Awards – Drama Desk". Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "1995 Awards – Drama Desk". Retrieved November fifteen, 2019.

- ^ "1996 Awards – Drama Desk". Retrieved Nov 15, 2019.

- ^ "1998 Awards – Drama Desk". Retrieved Nov xv, 2019.

- ^ "2001 Awards – Drama Desk". Retrieved November xv, 2019.

- ^ "2003 Awards – Drama Desk-bound". Retrieved Nov xv, 2019.

- ^ "2006 Awards – Drama Desk-bound". Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "2007 Awards – Drama Desk". Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "2015 Awards – Drama Desk-bound". Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "2017 Awards – Drama Desk". Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". Television Academy . Retrieved November xiii, 2019.

- ^ "Fellows". John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Obie Awards 1974". Obie Awards . Retrieved Nov xiii, 2019.

- ^ a b "1986-2000 recipients". The Lucille Lortel Awards . Retrieved November xiii, 2019.

- ^ "Pulitzer Prize Winners – Drama". Retrieved Nov 15, 2019.

- ^ "Obie Awards 1995". Obie Awards . Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Viagas, Robert. "Theatre Hall of Fame 1996". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ "Terrence McNally – Dramatists Social club Foundation". Dramatists Guild Foundation . Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Class Day and Commencement 2013 | Columbia Higher Today". www.college.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October fourteen, 2016.

- ^ "Social club History – The Lotos Lodge". world wide web.lotosclub.org. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved Oct fourteen, 2016.

- ^ "2018 Newly Elected Members – American University of Arts and Letters". artsandletters.org. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ BWW News Desk. "Playwright Terrence McNally Receives Honorary Doctorate From NYU". BroadwayWorld.com . Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Additional sources

- Grode, Eric (Fall 2000). "Testify Music: The Musical Theatre Magazine". Vol. Sixteen, no. Three.

- Straub, Deborah A. (1981). "McNally, Terrence, 1939-". In Evory, Ann (ed.). Contemporary Authors. Vol. 2. Gale Research Co. pp. 457–458. ISBN9780810319318.

External links [edit]

- Terrence McNally Papers at the Harry Bribe Middle, University of Texas at Austin

- Terrence McNally at the Playwrights Database

- Terrence McNally at the Cyberspace Off Broadway Database

- Terrence McNally at the Cyberspace Broadway Database

- Terrence McNally at IMDb

- New Plays And Playwrights – Working in the Theatre Seminar video at American Theatre Wing.org, January 2004

- Appearances on C-Bridge

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terrence_McNally

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Review 2018 Cranston Artist Exchange 13th One Act Play Festival"

Posting Komentar